From Bold Notion to Star Attraction, Griffith Observatory Has Opened New Horizons for LA

Essential to the narrative of LA, the Observatory is a testament to exquisite architecture (Art Deco with Greek elements) and “location, location, location,” says its long-tenured director, Dr. E.C. Krupp. From its perch on the southern slope of Mount Hollywood in Griffith Park, the Observatory is the center of the city’s universe. Lording over LA and eyeing a beaming Hollywood sign, it is the place where all points of view converge.

From the start, perspective was everything. At the time the Observatory was first suggested, by Welsh-born visionary Griffith J. For Griffith (“Col. Griffith,” as he liked to be called, despite holding no known qualifiers for the distinction), the idea of public science had been brewing for some years. A public observatory, on the other hand, was a pioneering idea for its day—a real shot at the moon.

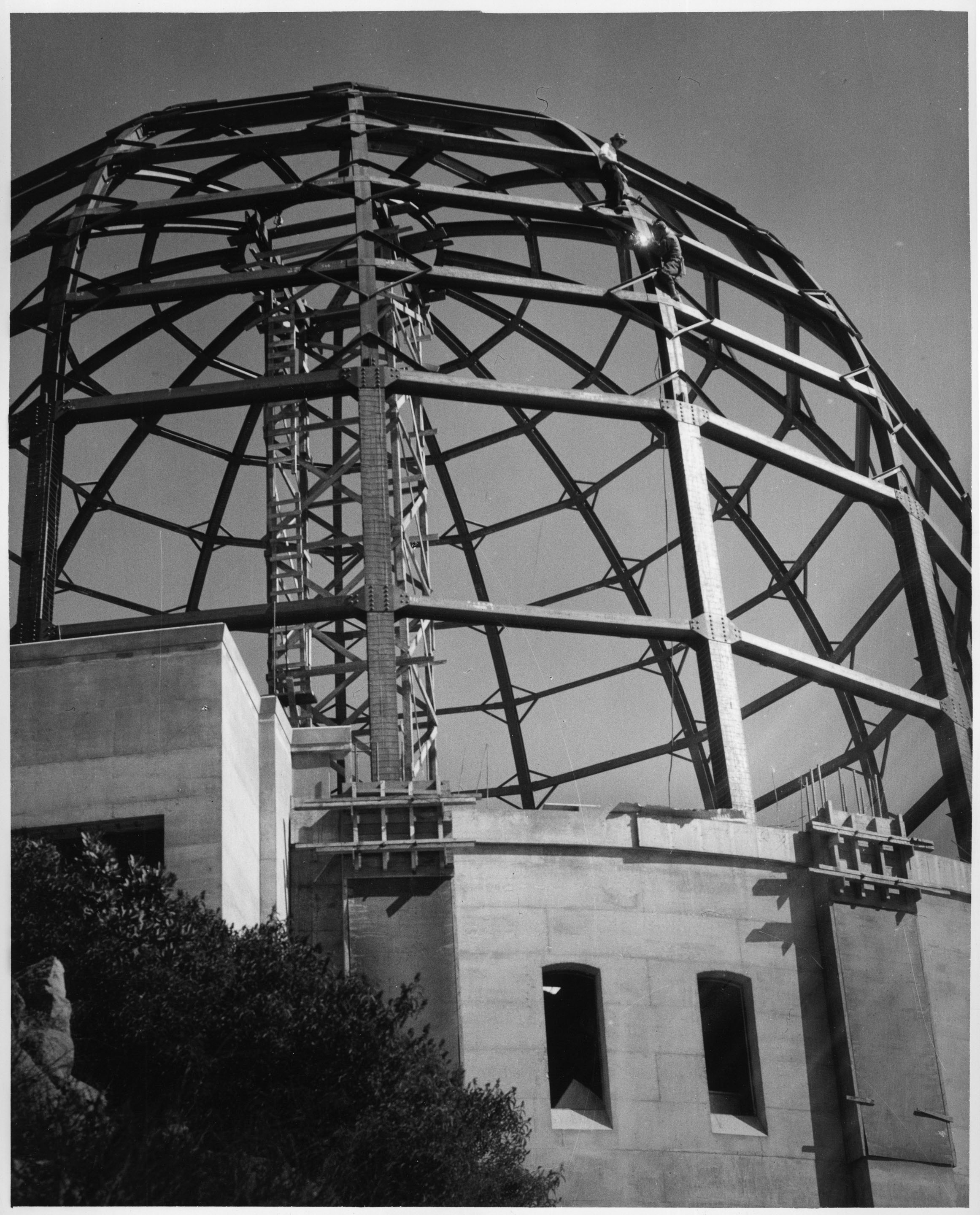

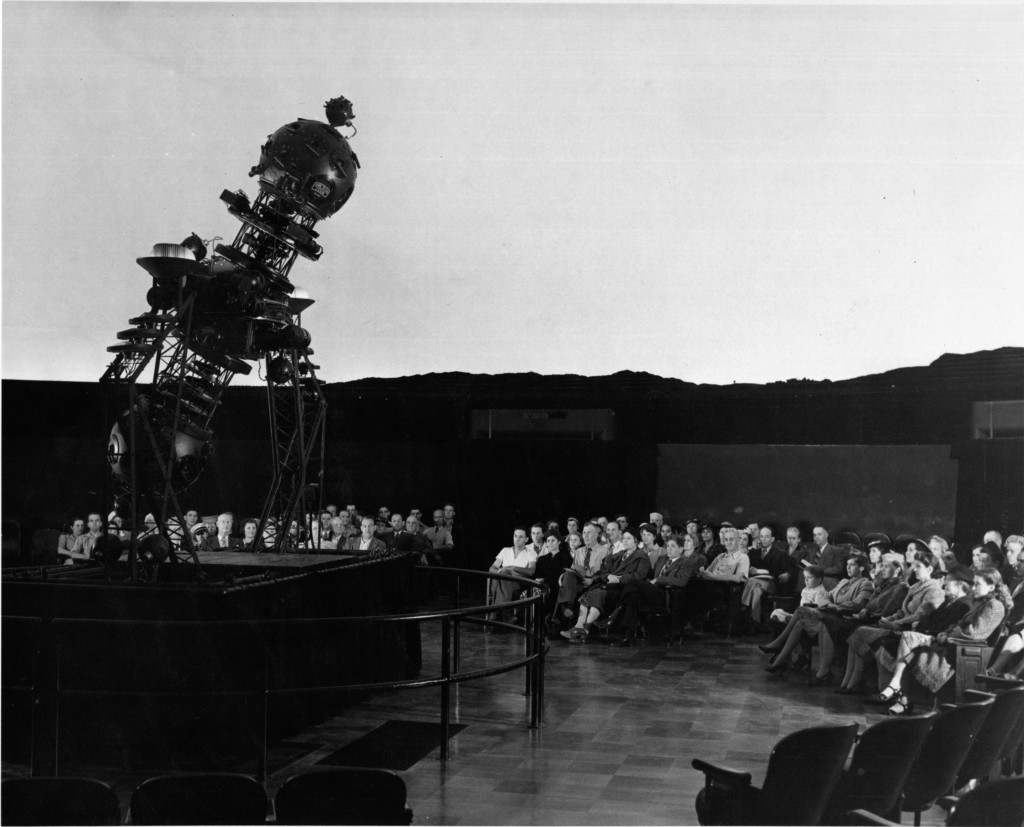

Still Col. Griffith persisted, and upon his death left behind a detailed directive for all aspects involved in its creation (to go with the sizable purse that he earlier gifted to the City of Los Angeles to build it). His plans called for an observatory that would make science accessible to the masses. Truly out of this world was its planetarium—just the third of its kind in North America, the first on the Pacific Rim.

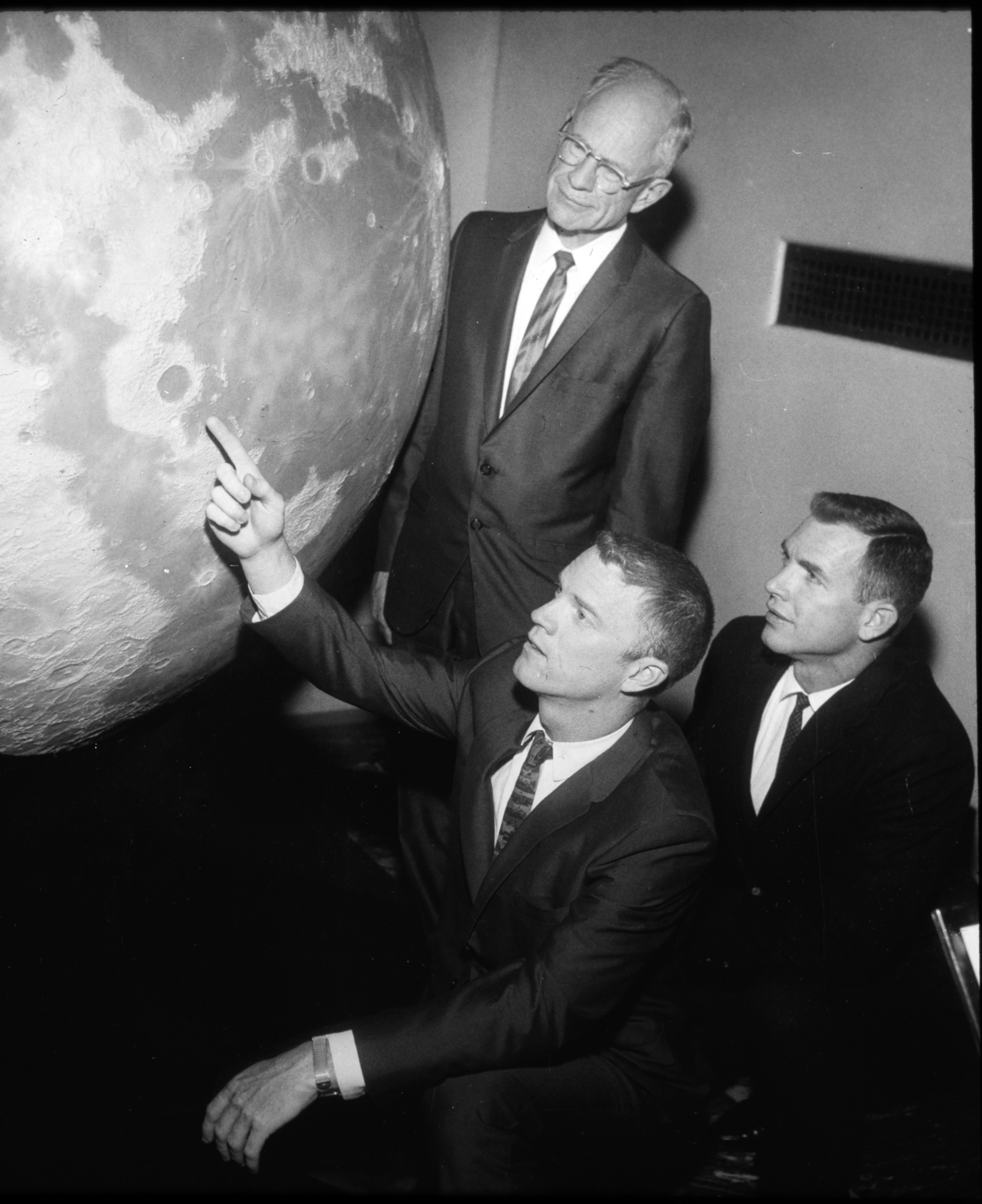

“Col. Griffith believed it was absolutely transformative to put people eyeball to the cosmos,” Dr. Krupp explains of the Observatory’s original intention.

“It was the experience of observing the universe that he wanted to transmit” and tap into our collective romance with the vast heavens above. And so the Observatory came to prominence, a bold and magnificent response to how we feel about a science that prompts the big, ponderous questions.

Public admiration is not without its price, however, and in 1978, four years into his post as director (after a stint as curator, where he worked from little more than a “closet” in the Observatory’s basement), Dr. Krupp penned his first memo suggesting that the Observatory be overhauled.

The renovation did come—in 2002—powered by $93 million and an epic effort to mobilize the initiative forward, in part thanks to the Friends of the Observatory, the institution’s base of support.

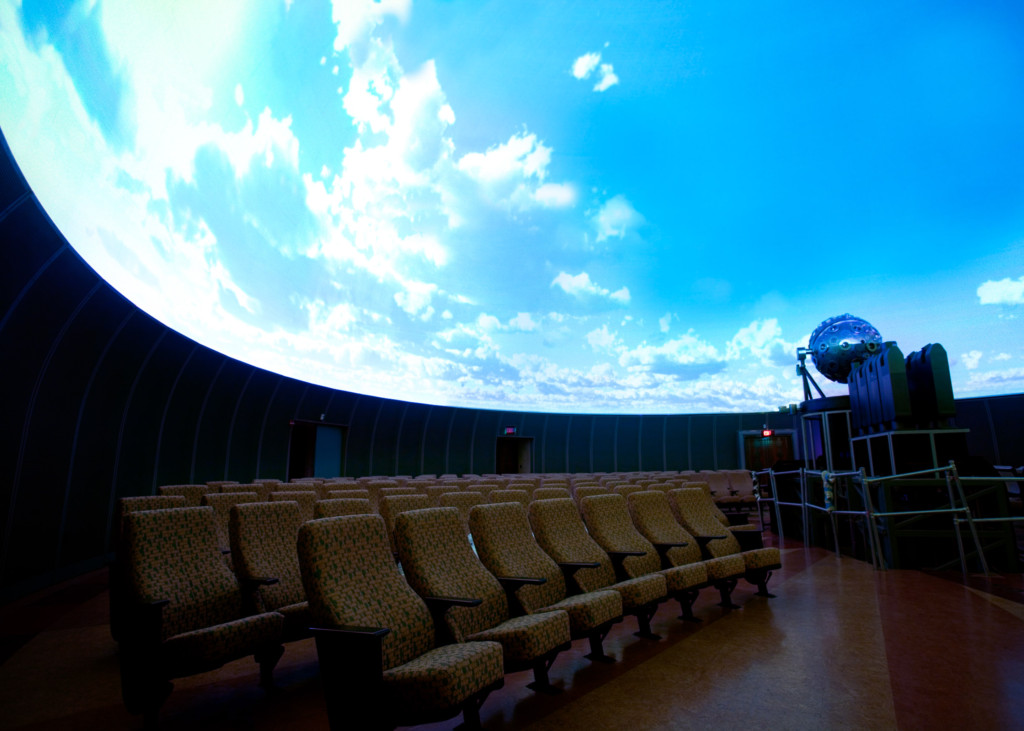

When the dust on the massive undertaking settled—one that included the addition of nearly 40,000 square feet of public space; an array of venues; and a state-of-the-art reworking of the Samuel Oschin Planetarium—the Observatory reopened in 2006.

Of course, in a show business town, the show must go on, and for the Observatory that means untold appearances in commercials, television shows and major Hollywood movies; the most significant being Rebel Without a Cause, the first film to cast the Observatory as the Observatory, not a fortress for serialized Sci-Fi fare. As the Observatory continues to nurture what Dr. Krupp describes as its “feedback relationship” with Hollywood, he boldly suggests it be given a star “on the Boulevard.”

Until then, there’s the total lunar eclipse on Sept. 27. As with major astronomical events in years past, Dr. Krupp expects thousands to descend on the Observatory to watch the eclipse, an opportunity to connect with the sky above and community below. When it comes to the Observatory, none of it—not the nerve of its founder, the public’s long fascination with the place, or its sheer endurance—surprises Dr. Krupp, who came to the Observatory as a UCLA grad student with professorial dreams.

Still, he says with a sigh, “Griffith Observatory has an identity of its own that insinuates itself into your heart and into your consciousness; you wind up having to do the Observatory’s bidding, and are quite happy to do so. It gets a grip on people, and I fear it got a grip on me.”

Just another mystery of the universe.

Photos courtesy of Griffith Observatory