How the Visions of German-born Architect Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe Would Re-shape Our American Cities

“Alone, logic will not make beauty inevitable,” architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe told LIFE in 1957. “But with logic, a building shines.”

And in his case, revolutionarily so.

Perhaps no one better understood how to positively exploit the potential of technology and engineering than Mies Van Der Rohe, a founding father of Modernist architecture who was central to the Great Age of the Skyscraper during the 1950s and 1960s—a time when many city landscapes would shift from horizontal to vertical.

His most famous commission was the Seagram Building (1958), a lean NYC tower famously sheathed in a bronze-and-glass curtain wall system—a singular Mies Van Der Rohe innovation that would usher in a new, prism-like look to high-rise buildings.

It was a first on many fronts: A series of bronze I-beams spanned the full height of the building, at 515 feet tall, while tinted plate glass, also at full height, ran between the beams. At each floor, skinny metal spandrel panels were placed horizontally to shroud the components that lay beneath.

Unprecedented at the time—and still glamorous and efficient 65 years later—Mies Van Der Rohe planted a seamless 38 floors on Park Avenue in a perfect expression of the International Style. One can mentally time-travel to when such forms never existed to grasp the curious feeling of discovery one would feel when faced with the vision of the Seagram Building for the first time; much like in 1908 spotting a brand-new Ford Model A speed by while still plodding along on horse and buggy.

Consistent with the radical innovation of its finished product—and as a testament to the remarkable talents of those involved, which included a select league of contractors and architects Philip Johnson, Ely Jacques Kahn, and Robert Allan Jacobs—the Seagram Building took only a few years to devise and construct. (In late 1954 Mies Van Der Rohe had been selected for the project by Phyllis Lambert, daughter of Seagram CEO Samuel Bronfman. By late 1957 the company was moving into their new building.)

It had been only three years, yet the power of Mies Van Der Rohe, then 71 years old, to conceive and execute such a thing had been decades in the making, starting not long after his birth.

Seeds of Mies: Shocking. Technically Buildable.

Born in Germany in 1886, Mies Van Der Rohe Van Der Rohe would study and labor in the workshop of his father, a master mason like his father before him, before beginning an architectural apprenticeship at age 15. In his 20s while working for Peter Behrens, a leading German architect and industrial designer, Mies worked as a construction supervisor for the German Embassy in St. Petersburg. (Not coincidentally, two other pillars of Modernist architecture, Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius, were also employed in Behrens studio during this time period.)

The significance of these years shows how the architect’s fundamental roots were in building—which is where they would remain.

Credit: Tom Ravenscrodt, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/legalcode.

“By actually working with stone, he acquired as a boy what many school-trained architects never learn—a thorough knowledge of the possibilities and limitations of masonry construction—and as a result of his early training he has never been guilty of the solecisms of ‘paper architecture,'” wrote Philip Johnson in a 1947 Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) press release on the eve of a Mies Van Der Rohe retrospective.

When it comes to tracing the pivotal seeds of the Seagram Building and other Mies Van Der Rohe landmarks—there are the detailed, early plans for his skyscraper visions, starting as far back as the late 1910s. His five famous projects. These plans were so-named for their startling innovation and influence; they were published frequently in Germany throughout the 1920s and a hundred years later are still considered touchstones of Modernist design.

His five plans included two soaring glass skyscrapers and a glass-and-concrete office building; all as stark and untraditional as spaceships—yet each expressed a singular concept expressed with disarming clarity, and distilled exactingly by Mies Van Der Rohe in charcoal.

“For we are not trying to please people,” he would later tell LIFE (Mar 18, 1957) of his design approach: “We are driving to the essence of things.”

As eye-raising as they were, the plans were no puff-smoke visions. They were technically buildable and would be realized as soon as conditions aligned, which in the case of the Seagram Building would occur some 40 years later on a different continent.

From the Bauhaus to the Seagram Building

Always concurrent with Mies Van Der Rohe’s architecture practice were activities in and around architecture, notably teaching. He was the final director of the Bauhaus, the hyper-influential German school that would finally shutter under pressure from the National Socialists.

Arriving in the U.S. in 1937 Mies Van Der Rohe settled in Chicago, where he would set up his architecture practice and lead the School of Architecture at Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) for a game-changing 20 years.

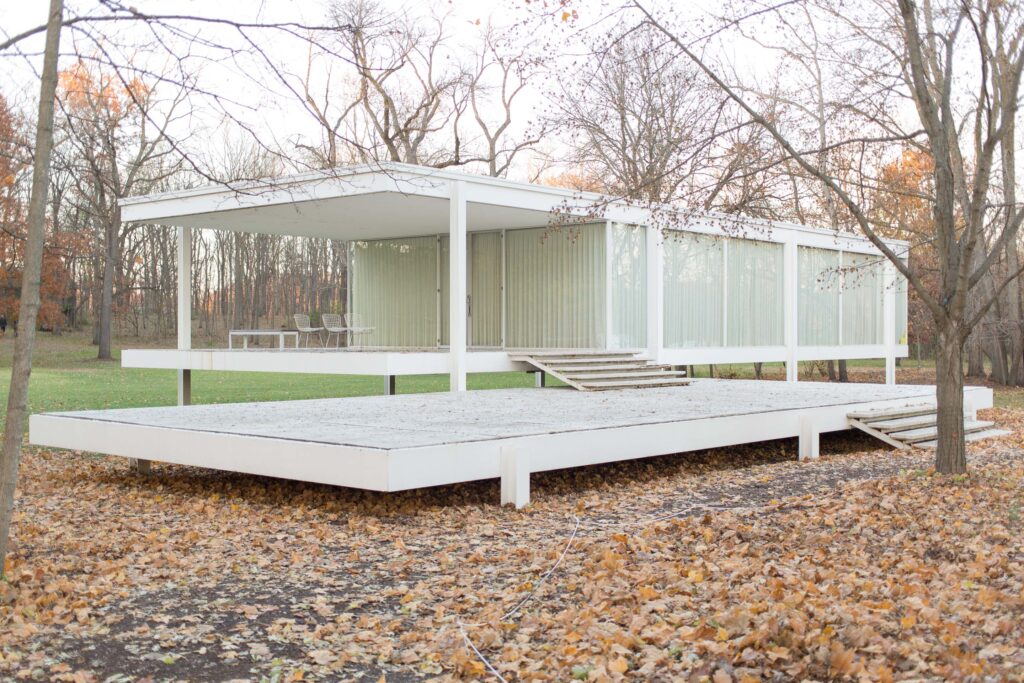

He implemented a curriculum—new for its time—that was multi-disciplinary, insisting that students were skilled across the spectrum of building, design and design thinking. This was another innovation, one Mies Van Der Rohe brought from the Bauhaus. And he left yet another legacy at IIT in the form of 20 International Style buildings he personally designed in the 1940s and 1950s. Then there was the Edith Farnsworth House, a rare residential project by Mies. (Completed in 1951, the starkly rectilinear glass residence is a National Historic Landmark that lives on as a museum.)

Around this time Mies Van Der Rohe also completed 860-880 Lake Shore Drive, a duo of clean-cut glass-and-steel apartment towers that captured the glittering city and the endless blue waters of Lake Michigan. This project was transformative to the city’s skyline and a full expression of what Mies had termed “skin-and-bones” architecture.

It was another first by the architect—an exciting new template for high-rise living filled with natural light, and connected to the city and nature all at once. And a fitting precursor to the Seagram Building, which he would embark on in only a few short years.

Today one can pass by a glass-clad high rise like the Seagram Building in any city and almost shrug at such a common sight, which is perhaps the point of the architect’s genius.

“Architecture is the will of the epoch translated into space,” Mies Van Der Rohe wrote in a book accompanying his 1947 MOMA show. “Until this simple truth is clearly recognized, the new architecture will be uncertain and tentative.”

For he was a man who fully grasped the will of his time—and knew precisely when to realize the skyscraper visions he’d held for over 40 years.

“Not yesterday, not tomorrow,” he reflected, “only today can be given form.”