Table of Contents

Los Angeles Lakers Coach Byron Scott on Performance, Private Passions & Keeping His Famously Even Keel

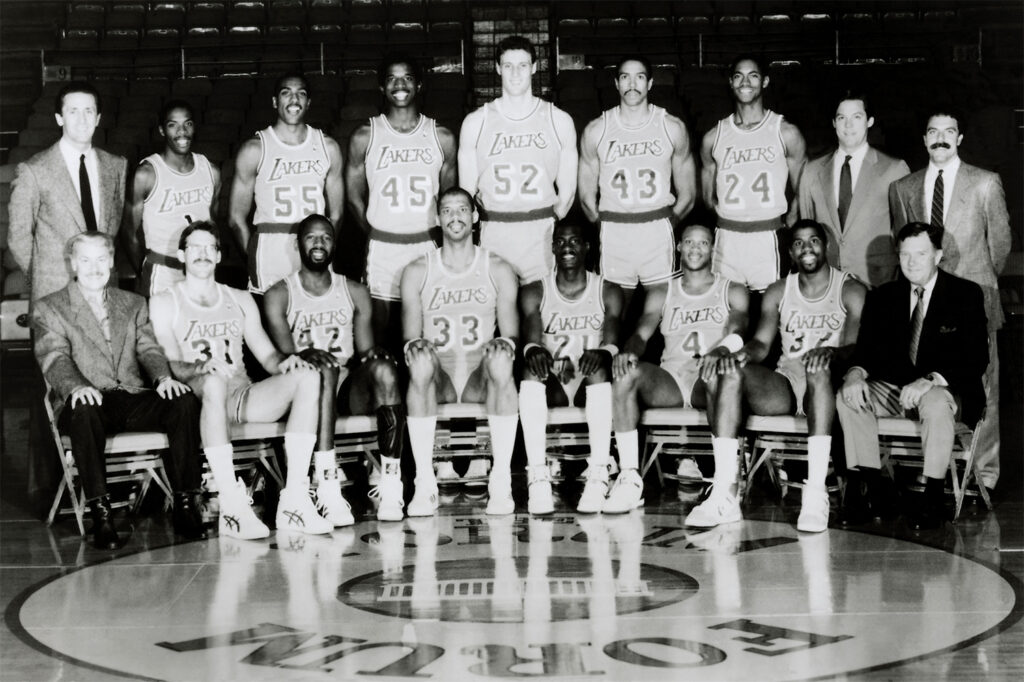

The Arizona State star basketball player Byron Scott was a transplant from Inglewood, California, who had dominated the Sun Devils squad since 1979 with record-busting seasons that earned him a place in the university’s Hall of Fame.

It also gained him an entrée as first inductee into the school’s Pac-10 Hall of Honor, among a heap of other accolades. At the moment, though, he was just waiting on some news.

In 1983 Byron Scott Received a Phone Call That Changed His Life

“I was 21 years old,” recalls Byron Scott, settling into his chair.

“I had been drafted by the Los Angeles Clippers, which was one of the happiest days of my life. To be drafted into the NBA, that was a goal of mine for years. Ever since I was 8 years old, I always told my mom and dad I was going to play in the NBA, so that was a goal I was about to see come true.”

“Then my favorite team, the Los Angeles Lakers, called me and told me they’re about to make a trade,” he continues.

“I nearly died and went to heaven when I got the call that I was traded to the Lakers. It was obviously the best thing in my life. I was a boy from Inglewood, California, who had been watching the Lakers for years, and now I get the opportunity to play for my home team, the team that I love the most.”

In the 30 odd years since that call, Byron Scott has held onto a continuum of success—first as a player, then as a head coach—in a demanding and sometimes fickle industry. Here, he shares some secrets to his longevity.

Powered From Within and Above

Novelist George Orwell once famously said, “At age 50, every man has the face he deserves.”

If true, Byron Scott has piled up his fair share of merit. His complexion has the smooth suppleness of a man at least a decade younger. His hazel eyes strike amber in the sunlight and he’s maintained the taut physique of a disciplined athlete.

“I was nervous my first game—until I got on the court and the ball was thrown up into the air,” says Byron Scott, recounting his fledgling steps on an NBA court during game time.

“You forget about everything else that’s going on and you really focus in on what you’ve got to do.”

It makes sense, considering that the young athlete had already logged countless hours of his life on the basketball court before he strolled into the Great Western Forum, a bona fide pro who could snap into game mode in an instant. But there was something else at play—namely, the cool assurance that come what may, everything would be just fine.

“Something my dad and mom taught me from a very early age is to shoot for the stars,” says Byron Scott. “They always told me to go at it 110 percent. But if you don’t make it, at least you can look in the mirror and say, ‘You know what? I gave it everything I got.'”

In other words, instilled in Byron Scott, perhaps before his fingers had ever touched a basketball, was the idea that winning in the conventional sense did not automatically mean that one had won in the personal or spiritual realm. And vice versa.

“I have an inner peace within myself that keeps me grounded, and keeps me level,” Byron Scott says slowly. “I never really get too high or too low. I kind of take everything as it comes. Even during stressful situations I always want to have an even keel.”

An asset of temperamental gold for anyone, it’s doubly so for any sports professional on the front lines, where one might be lauded as a miracle-maker one day, and branded a pox on the game the next.

This internal balance, or equanimity, is an indelible part of Byron Scott. And sheer talent aside it, along with his faith and resolute attitude of gratitude, accounts for much of his long track record.

“I truly know that everything that I’ve gotten in life, I’ve earned. I also know that a lot of what I’ve gotten is because I’ve been very blessed from up above,” he says earnestly, pointing skyward.

“My Heavenly Father has blessed me tremendously to give me the talents he has given me, and I don’t take that for granted.” But no man is an island, or in this case, just an athlete and a coach. And there is more to this man than the game.

Big-time Love

This past August Byron Scott kicked off the inaugural year of his new youth basketball camp, which helps boys and girls ages 8 to 17 hone the fundamentals of the game, from handling and passing to footwork and rebounding.

“The kids were great,” reports Byron Scott. “Just being in the gym for me is heaven, and the thing that I love most is interaction with the young people, being able to talk to them on a day to day basis, and for them to get to know me a little bit.”

“At the end of the day, they see this guy on TV and now they can relate to him a little bit more because they’ve spent a week with him, and they know he’s more than just a basketball coach.”

It’s a youth-focused endeavor in a long stretch of them for Byron Scott, who started the Byron Scott Children’s Foundation in 1986 (now the Byron Scott Children’s Fund), fueled by a desire to help children with cancer.

“A young man named Marshall Brady, his family sent me a letter when he was 3 years old and in the hospital in remission,” says Byron Scott. “I went to visit him, fell in love with the family and decided right then and there we had to do something for kids.”

Byron Scott reports that Brady subsequently kicked cancer and went on to graduate from USC, where he played in the band. Meanwhile, Byron Scott’s organization, with its longtime focus on children’s health and cancer research, has been undergoing a shapeshift.

“I still have a big-time love for children,” he says. “Now I am looking for different avenues to try to reach the kids.”

A Suit Tells a Story

Byron Scott’s consciousness of his good conditions makes him quick to support those who serve on the front lines, the military.

“The reason that we’re here doing this today,” Byron Scott says, “is because of the things they do on a day to day basis, and the way that they sacrifice their lives for their country so we can sit here today.”

Byron Scott’s appreciation currently takes the form of participating in a Suit for a Suit, which is a pro-veterans organization that sources smart business attire for returning soldiers who are headed to civilian job interviews.

“They got in touch with me a little over a year ago. Once I knew it was legit I wanted to get involved. I felt that, I got a ton of clothes, let me just give as many suits as I can to our soldiers.” says Byron Scott, who personally has a yen for clothes, and understands the transformative power of dressing well.”

“I don’t think we understand how tough it is,” he says of soldiers transitioning back to civilian life. “I think we as citizens should do everything we can possible to help them to re-adjust back into society, so they can live a very prosperous life.”

The No-stress Express

Another keen passion of Byron Scott’s is music, a topic that visibly energizes him. “I like listening to a little bit of everything,” he says. “Even rap. But R&B is my love, contemporary jazz is my love, and it’s something I want to get a little more involved in.”

He listens deeply, immersing himself in the mood of a composition, plucking out lyrics and floating along with lilting melodies. Perennial favorites include Anita Baker, a personal friend of Byron Scott’s, along with groove-makers from the 1960s and 1970s like The Isley Brothers, The Whispers and Earth, Wind & Fire.

“I really love R&B,” says Byron Scott with a grin. “It probably goes with my personality. I like it nice and mellow and smooth.”

Byron Scott’s interest in music has lately gone beyond the aficionado stage. He’s the executive producer of a new smooth jazz-funk album by Rock & Roll Hall of Fame bassist Chip Shearin.

“He’s one of the best bass players in the world, but he’s always worked with other people,” notes Byron Scott.

“He decided to go on his own, and I’m one of the guys who said, ‘I got your back. Let’s do this and see what happens.'”

Both Sides Now

Meanwhile, his day job since that fateful 1983 phone call has revolved, year in, year out, around pro basketball. An NBA player for 14 seasons—11 of them with The Lakers—Byron Scott kicked off his coaching career in 1998 as assistant coach of the Sacramento Kings. In 2000, he took over as head coach of the New Jersey Nets. Fourteen years later, after returning to his home team, the team he loves the most, The Lakers, for a second act.

As a coach, Byron Scott’s leadership style is embedded with the experience of having been one of the guys lacing up his sneakers and heading onto the court each night. The difference between being a player and a coach? Shifting from a singular perspective to a collective one.

“As a player, I always felt that I could affect the game because I’m out there on the floor,” Byron Scott explains.

“As a coach, I have to rely on these guys to affect the game and have faith in me that the plays we have presented to them, they can go out and implement. As a player, you only have to worry about you, but as a coach, you got to worry about the whole team. You’ve got to somehow convince them that the ultimate goal and the agenda should only be to win.”

To win on the courts, yes. And if Byron Scott had his way, for each to win in every other meaningful aspect of their life.

Photography by Paul Jonason