The Artistic Traditions of Neighboring Cultures Collide in a New Exhibition at LACMA

The vibrant showcase of objects and ephemera from its focal provenances is, with broader consideration, a cultural exchange between domains with richly interlinked frontiers.

“California and Mexico are irrevocably joined by geography, culture, and economics—ties that precede and transcend modern political borders,” say Found in Translation co-curators, Wendy Kaplan, department head and curator, and Staci Steinberger, assistant curator, both of the Decorative Arts and Design department at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA).

“For centuries, people have moved back and forth between the two places, bringing objects, styles, and images whose meanings were shared as well as altered. This is the first exhibition to explore the full range of design and architecture dialogues between California and Mexico in this period.”

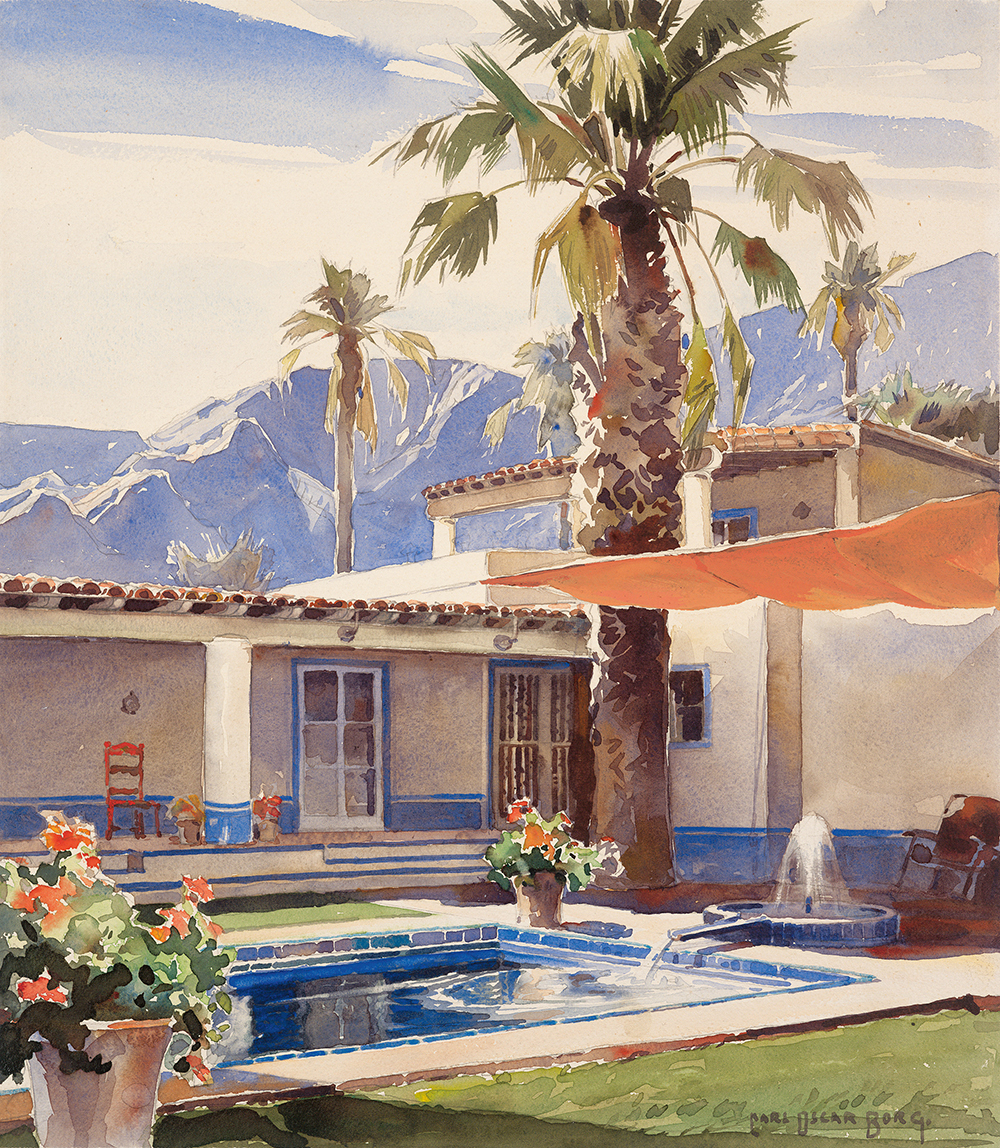

The show studies these interdependencies through the themes Spanish Colonial Inspiration, Pre-Hispanic Revivals, Folk Art and Craft Traditions, and Modernism.

“All explore how in California and Mexico, design and architecture are strongly rooted in a sense of place, with local materials and traditions used to form a culture of specificity rather than an ‘international style,’” notes Kaplan.

“And each found a more distinct voice through ‘translations’ of the other.”

Comprising the exhibit—a strong underscoring of LACMA’s dedication to Latin American art—are 250 pieces ranging from furniture, metalwork, and ceramics to textiles, paintings, posters, and more by 200-plus artists, architects, designers, and craftspeople. So rich in design and architectural discourse is this trove, Kaplan and

Steinberger find it difficult to play favorites. “In a show like this, it’s so difficult to choose!” say the curators, who nonetheless note a loan never before shown in the United States—a Bench from Casa Zuno, Guadalajara, c. 1925—as a piece of particular interest.

Hailing from a house designed for José Guadalupe Zuno, once governor of the state of Jalisco, the bench was built right after the Mexican Revolution, when intellectuals championed neocolonial style as distinctly Mexican.

Though its design recalls furnishings from the Colonial period, it replaces religious iconography with socialist imagery. Found in Translation also surveys the ways that California artists, designers, and craftspeople embraced facets of Mexican folk art in their work; most surprisingly Japanese-American sculptor Ruth Asawa, known for her biomorphic hanging sculptures made from an intricate handmade mesh of wire loops, a basket-making technique she learned in Toluca.

“Asawa’s use of the loop is transformative,” explains the curators.

“She took a utilitarian structure and made a wholly original, purely abstract body of work. The example we’re borrowing for the show comes from the collection of visionary architect Buckminster Fuller, who was one of Ruth Asawa’s teachers.”

Also of interest is material from the Summer Olympics in Mexico City (1968) and Los Angeles (1984). As sprawling metropolises, both cities employed a similar design strategy and used environmental graphics to visually unify the many Olympic sites. Look for posters, a map, a fabulous hostess dress from Mexico City, and posters and sonotubes (supersized painted cardboard tubes) from L.A. In other words—or en Otras Palabras—the best of both worlds.

Found in Translation: Design in California and Mexico, 1915-1985 will run from September 17 through April 18, 2018. LACMA.org