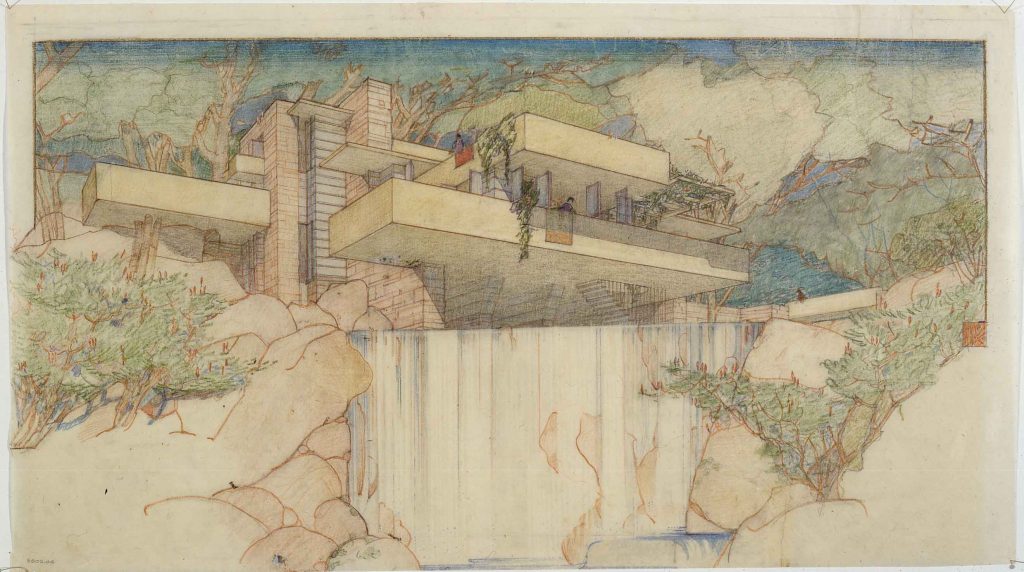

The consummate example of Frank Lloyd Wright’s organic architecture, Fallingwater is the architect’s masterwork—and the full expression of his nature

He looked at the site and saw it: a house emerging from the hillside, its peninsular planes seemingly suspended and staggered downward to emulate the stony cliff over which rushes a surge of mountain stream. The elevations, the geometry, the complexities, he saw it all. A vision that only a true visionary possibly could.

But Frank Lloyd Wright, well into his sixties at the time, produced nothing tangible for nine months thereafter. Everything was in his head. The commission, he knew, had the potential to reignite his career, one that he began when America still turned to horses for transport.

And here it was, 1934, the Great Depression, with Frank Lloyd Wright in the wilderness of his professional life, having completed just a handful of commissions in the last 10 years. Many wondered if Louis Sullivan’s protégé, who helped pioneer the Prairie School and designed both the Unity Temple and the Robie House, was all washed up.

Not Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann, however, who commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design for them a weekend home on a wooded site in the mountains of western Pennsylvania. Prosperous department store owners, they were a good match for Frank Lloyd Wright in every way, both worldly, with operations in Pittsburgh and an office in Paris. Kaufmann was a larger-than-life character who loved big ideas and interesting people.

His wife was a woman of great taste and an exceptional eye; she was devoted to beauty and ran a specialty shop with an international selection of haute couture on the 11th floor of the Kaufmanns’ department store. They also shared the architect’s love of nature and appreciated his honest expression of materials and form. They showed Frank Lloyd Wright the site, then waited.

Myth often has it that Frank Lloyd Wright conjured the design for Fallingwater almost from thin air. But three of his apprentices—witnesses to the following events—told it somewhat differently. Kaufmann, in an effort to get something out of Frank Lloyd Wright, made a series of calls to Taliesin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s home in Wisconsin, telling the architect he was en route to see the plans.

On the day Kaufmann was to arrive, “Frank Lloyd Wright finished breakfast and went into the drafting room with his apprentices around him,” relays Lynda Waggoner, director of Fallingwater since 1996, who knew each apprentice.

“They said all they could do was sharpen pencils. But because Frank Lloyd Wright had this incredible ability to design things in his head, I’m sure that during that nine-month gestation period he thought through the night, did a little sketch here and there, so that by the time Kaufmann arrived to see the preliminary sketches, he just drew it all out.” In an unpublished essay Kaufmann later wrote for an exhibition at Fallingwater, he confessed to not fully seeing the house at this stage.

Which might explain the surprise the Kaufmanns felt when they realized that Frank Lloyd Wright’s final plans did to not include a view of the site’s natural wonder, which they loved and clearly expected to see from the house. A terrific salesman, Frank Lloyd Wright reminded the Kaufmanns that the waterfall had always been a destination point for them on the site. They had picnicked there and watched the falls. His plan would help retain that sense of destination. Because if they were always looking at the falls, he explained, it would become commonplace. Wright would have his way.

In 1938, after a few rough patches, Frank Lloyd Wright realized what is an ingenious configuration of structure and site that exposed the depth of his unorthodoxy and architectural gifts. Fallingwater had traces of his earlier work (the cantilever, taken to its absolute limit with this project, and concrete, a modern material he used early in his career), but was unlike any building he’d ever done—the very model of organic architecture, which for him meant the merging of architecture and nature.

“But it’s more than that,” Waggoner explains.

“It’s a principle; a holistic view of the world that man has a place in nature…Frank Lloyd Wright believed that there should be as many styles of buildings as there are types of people, and they should be individualistic.”

Accordingly, Fallingwater stands alone. With its exaggerated planes of reinforced concrete and bands of steel-framed windows, the house is best understood as a response to what the architects of the International Style were doing. It is exceedingly geometric and horizontal, characteristic of that style, but with a humanity often lacking in the buildings it produced.

It was all Frank Lloyd Wright: singular, suited to his client, and of both the times and the spirit of the place.

Fallingwater offers a contrast of experiences and juxtapositions—light and dark, danger and safety, smooth concrete and rough stone—that give it a wonderful richness. Passing through the front door, which is hidden between two walls, is a bit like entering a cave, sheltered and safe, but glance diagonally to the opposite end of the room and the outstretched terrace beyond and it’s open and bright. The exposure conveys a sense of danger that one has when looking at Fallingwater from a distance, its serrated arrangement appearing unanchored.

Like the Kaufmanns, one expects to see the waterfall, but doesn’t, not for a long time, by design. “Frank Lloyd Wright was really smart in his sense that we all have a final impression of something—so he saved it for the very end, so that the waterfall would be the final memory one has of the house and not overshadow the experience of it,” Waggoner explains.

“Because when you go through the house, it is very intimate, like a meander through the woods. You go around corners and things open up and close down. It’s dark and light. You walk the terraces. Then, when you go down to see the actual view of the waterfall, you think, this is just incredible, because you have come to understand the house. So he knew exactly what he was doing when he designed it.”

Fallingwater reestablished Frank Lloyd Wright’s place in architecture, exactly as he hoped. He appeared on the cover of TIME Magazine with the house behind him and, at age 67, embarked on the most prolific period of his career, completing the Johnson Wax Building, the Guggenheim and many more buildings. Mostly, though, Fallingwater exemplified what Frank Lloyd Wright spent his entire career trying to create: a distinctly American architecture.

It has all the features of this vernacular—a connection to the setting in a way that blends the two together; an open plan; the geometrizing of elements; a play with interior volume; and unity through a limited palette of materials—to touch something deep within us that Frank Lloyd Wright understood intuitively: the desire to reclaim our place in the natural world.

“That’s what Fallingwater does for us,” Waggoner says. “It’s the physical demonstration of what freedom is about. It teaches and amazes. I think that’s the testament of a masterpiece.”

Fallingwater | fallingwater.org

Photographs Courtesy of the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy