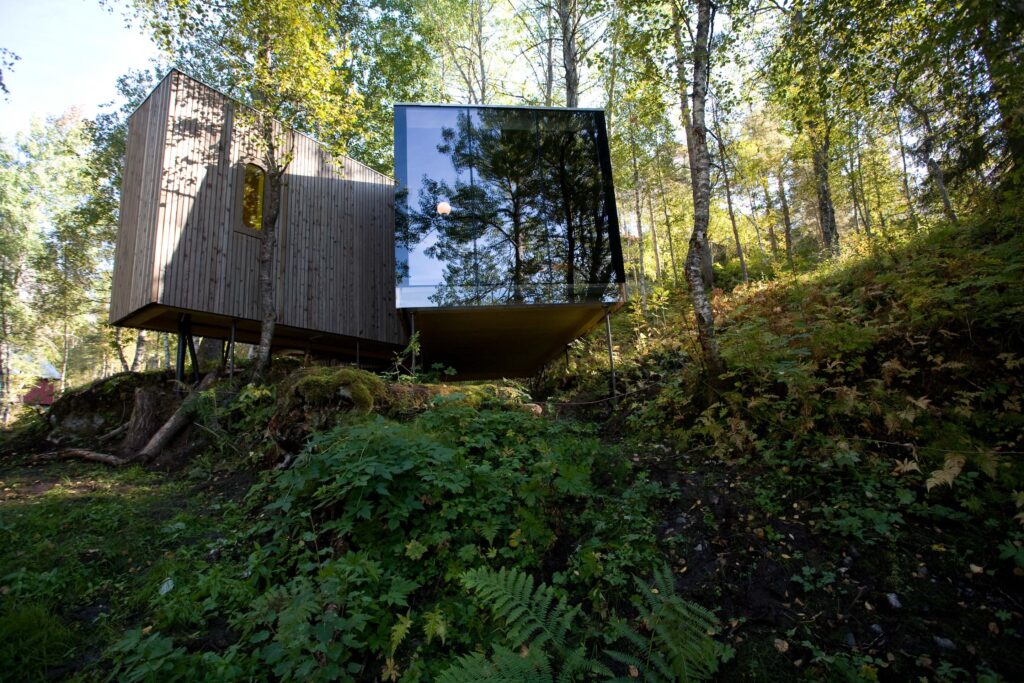

A Wildly Experimental Architecture by Jensen & Skodvin Reflects the Purity of Its Resplendent Norwegian Surround

As a thaw falls over the sublime wilds of northwestern Norway, a reawakened Valldal valley reveals an almost unfathomable immensity: soaring mountains, bright sky, and a frothing turquoise river coursing through a canvas of green tones and timber. This immaculate opus represents a kind of clockwork that resets itself to the tenor and splendors of a new season, each more beguiling than the last. One Nordic refuge is witness to it all—the Landscape Juvet Hotel.

Set in a nature reserve, this prize-winning pile by Norwegian architecture firm Jensen & Skodvin is not a conventional hotel. Nor would it be. Its owner, after all, is not a conglomerate of homogenous megaresorts, he is Norwegian Knut Slinning, whose profound and abiding ties to the land and locality alike make him a passionate advocate for both. In bringing his clarity of vision and reverence for originality to the project, the result is a deeply authentic, organically drawn architecture based on keeping things simple and exploiting the scenery while helping to preserve it.

“Conserving the site is a way to respect the fact that nature precedes and succeeds man,” Jensen & Skodvin expressed in their program notes.

This is not just a poetic frame of an enduring truth. It is the ethos that drives the architecture—the foundation on which it is built. The architects employed a procession of sustainable strategies in the construction of the hotel. None is more crucial to a virtuous outcome than distributing the individual dwellings—structures that are propped up on massive steel rods drilled into the rock bed so as not to damage the immediate environment—across the site.

“The Juvet pioneered a sustainable, conservation and ethical approach to building a hotel in a wild spot of nature,” explains Iain Ainsworth, founder of The Aficionados community whose eclectic emporium of exceptional and even curious hotels include Juvet. “The concept is as indigenous as the trees surrounding it; in essence, it is straightforward,” he continues. “That thought allowed the design and architecture to dialogue with the surrounding nature rather than disturb it.”

The purity of the landscape extends to the architecture itself—a series of modernist pine and glass constructions (including a few high-up Birdhouses modeled after traditional Norwegian loghouses and a larger four-bed chalet called the Writer’s Lodge). All are orientated toward a vivid and stupefying view.

“It’s like being a voyeur of nature,” Iain Ainsworth says of these radically spartan environments.

That their dark-toned and elaborately glassed interiors are rigorously minimalist is not from aesthetic preference, but to maximize inhabitants’ connection to both nature and the view. As evening descends, the space morphs into a kind of cocoon.

“All you see is darkness and stars,” says Iain Ainsworth, singling out a sliding hatch situated at pillow level as a particularly thoughtful touch that “enables you to listen to nature as your sleep under the duvet.”

A full immersion into the landscape without leaving a lasting impact. Not all is modernist, at least in the historical sense. The Barn, a century-old farm building, was restored and reimagined for new use: its former pigsty is now the kitchen, its cow byre a dining room, and its hay store an outdoor lounge area.

The hotel’s conference room, meanwhile, despite that staid and ultimately unexciting classification, is more of a spectacle than one expects: still essentialist in character but appointed with a breathtakingly high ceiling featuring an intricate system of beams, exposed walls and another floor-to-ceiling glass window that gazes out to a beguiling twist of river. Adding to this, the Bath House brings forth a hot tub, steam sauna and silent room.

Pause to consider: a silent room. When Juvet was first built just over a decade ago, the idea of a complete disconnect-to-reconnect in a monastery-sized space might have seemed a little eccentric to some. Maybe even indulgent. History holds a different view of seeking expansion in a simple structure: Dylan Thomas wrote in a boathouse. Thoreau had his cabin. In today’s hurried existence, Juvet is as much a place as it is a pilgrimage.

In terms of seclusion, the faraway refuge really is removed from much of the world. Those new to Juvet’s blazingly futuristic forms might even think it of as another world entirely, one more in keeping with the sci-fi thriller Ex Machina, in which the hotel made a memorable cameo as a billionaire’s abode and, in the less fictional distance, in an episode of HBO’s Succession.

But this highly scrutinized consideration of space is stubbornly rooted in the terra firma of our time, offering lessons already learned remembered anew: Nature is precious. Connection is a luxury. Less is more.

Jensen & Skodvin | jsa.no

The Aficionados | theaficionados.com

Photos: Juvet Landscape Hotel