Reflecting on Vincent van Gogh’s enigmatic Irises at the Getty Museum

And though it bears the distinction of being one of the priciest paintings ever sold, its true value is incalculable. Truly great are the artists whose work stirs a visceral reaction long after they’re gone. This is certainly true for Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh, his triumphs and travails equally studied, and his paintings, whether pastoral or portrait, still fixtures of fascination for artists and art lovers alike. In Los Angeles, it’s the Post-Impressionist’s Irises that inspires.

As one of the crown jewels of the Getty Collection, the museum acquired Irises in 1990. And though it bears the distinction of being one of the priciest paintings ever sold, its true value is incalculable.

“The painting has an extraordinary sense of presence,” explains Kate Flint, chair of the Department of Art History at the University of Southern California. In part because when Vincent van Gogh painted Irises in 1889, he was particularly vulnerable— and remarkably prolific.

Within a week of voluntarily committing himself to a Saint-Remy asylum, he painted the landmark work in the hospital gardens, going on to produce many more pieces, including The Starry Night.

The irises themselves, very many of them just passing their prime, seem anxious, especially by way of contrast with the rigid orange marigolds behind them. There’s an urgency to the brushstrokes, too, that makes it hard to read this as a tranquil piece.

Given the fragility of Vincent van Gogh’s mental state at the time he painted Irises, one might naturally view the work as a reflection of his troubles. Look past the bold brushstrokes, the vivid color and the monumentality of the flowers, and an uneasy mood emerges.

“Blue is normally associated with meditation and thoughtfulness and tranquility, but the wavy leaves and stems are anything but quiet,” Kate Flint explains.

“The irises themselves, very many of them just passing their prime, seem anxious, especially by way of contrast with the rigid orange marigolds behind them. There’s an urgency to the brushstrokes, too, that makes it hard to read this as a tranquil piece.”

Rather than creating a still life effect, the flowers animate the painting with a sense of movement—“they’re growing, living, and not very happy sentient things,” offers Kate Flint.

Considering Vincent van Gogh’s isolation when he painted Irises, the work’s lone white iris seems particularly poignant as a symbol of his seclusion, although without textual proof, it’s at best a projection.

The bloom may have simply caught the eye of the artist, and it’s our own restiveness responding. So much of what we choose to see in Irises is conjecture, but its enduring pull is very real. Hence, those who flock to the Getty see a painting that we can only ever hope to partially understand.

But, Kate Flint adds, “[Irises] is a terrific example of how we can be strongly affected when we first see a work of art without necessarily knowing why. It makes us stop, and look, and think… about its relationship to us, and to our feelings.”

Irises, 1889, Oil on canvas

74.3 x 94.3 cm (29 1/4 x 37 1/8 in.)

The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

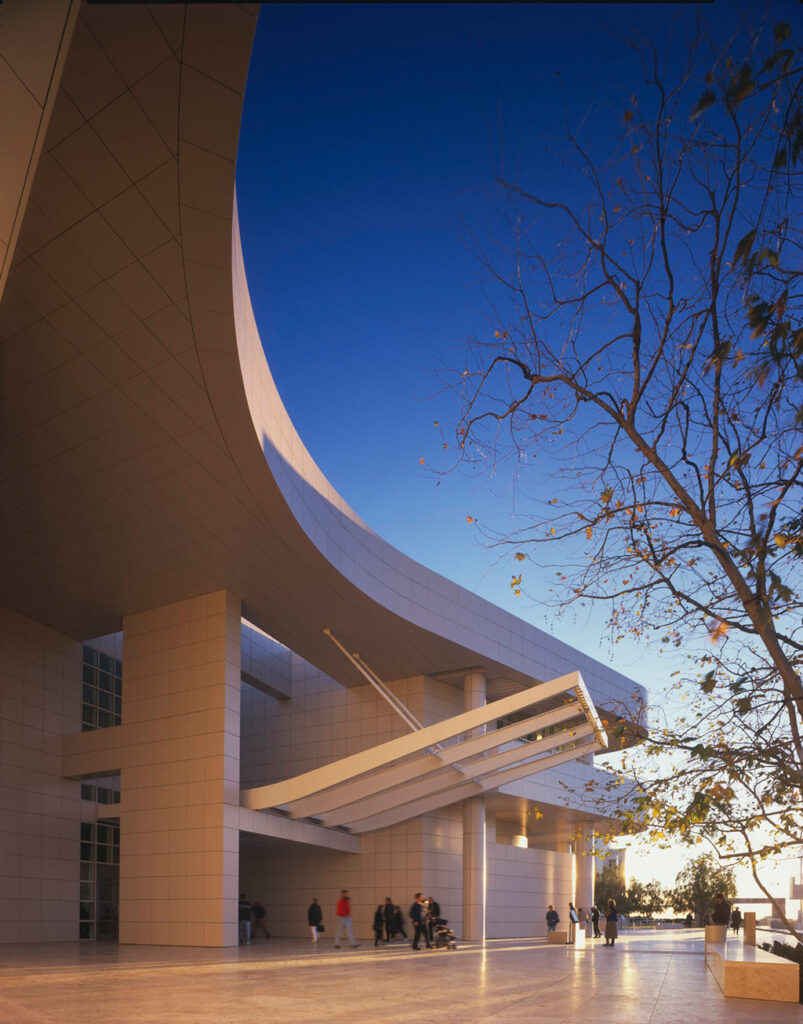

Architectural Images © J. Paul Getty Trust

Irises images Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program