In the annals of legendary Los Angeles architecture, ultra-exclusive Trousdale Estates is still the pinnacle of elevated living

With 535 homes scattered across some of the most storied sites in Beverly Hills, tony Trousdale Estates is as bright a star as the luminaries who have famously called it home. And what homes—imperious places with square footage and city views to spare. Featuring museum-quality architecture from some of the most celebrated names of their day—from Wallace Neff and A. Quincy Jones to Cliff May and Lloyd Wright— Trousdale Estates represents social prestige on an unprecedented scale.

To own a trophy home here was—and still is today—to arrive in the most glamorous fashion one could possibly conceive.

The one who actually did, though, was Paul Whitney Trousdale, a prolific developer steeped in Southern California real estate, whose outsize ambitions resulted in an ever-increasing number of aspiring projects all the way to Hawaii.

He saw the promise, envisioned the place where he, too, would eventually commission a home. Although in some ways obsessed with his place in the establishment, Trousdale was progressive in matters of business, which he proved in 1954, negotiating a deal for 410 acres of Doheny Ranch land above Beverly Hills that, with a miracle of engineering, he would help transform into the dream development that bears his name and his imprint.

Trousdale Estates did not just proclaim exclusivity—it enforced it.

Building codes were strict (home plans had to be approved by a master architect) and residents were high-powered. Its tagline promising “life above it all” was more shout than insinuation: Trousdale is the place for the elite went the thinking. Dinah Shore and Groucho Marx bought lots. Moguls moved in. By the 1960s, Trousdale’s roster of residents included Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley and Richard Nixon.

With pedigree nonpareil, Trousdale homes were starchitected showpieces where everything was bigger, grander—the marble gleamed, front doors stretched to the heavens, pools had sex appeal.

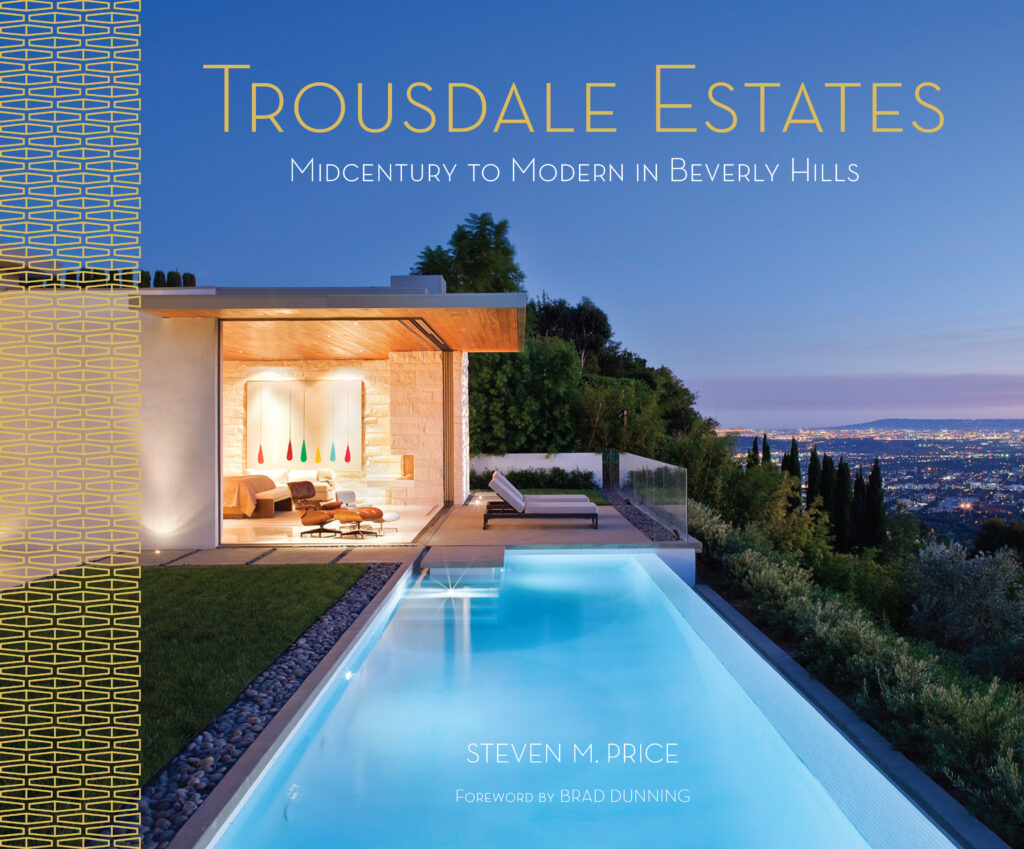

Still synonymous with the city’s rich and powerful, the Trousdale Estates of today signifies more than mere flash—no longer is it just that brash social experiment lording over all in Beverly Hills. Despite a number of teardowns in recent years, the development is getting its due as a significant architectural record via the forthcoming new book, Trousdale Estates: Midcentury to Modern in Beverly Hills, which details the enclave’s history down to the studs and is certain to appeal to the whole new generation of midcentury enthusiasts recognizing Trousdale as incubating some of the finest of architecture from the period.

On the eve of the book’s release this January, author and preservation consultant Steven M. Price reflects on the most exclusive luxury community in Los Angeles.

Of all the architecture in L.A., what compelled you to write a book about Trousdale Estates and how long did it take?

Honestly, it took me 40 years. But I thought, Trousdale started coming back around the year 2000 and I grew up studying its architecture; so in 2008, when nobody had written a book about it, I said to myself, I’ll do it as a hobby! Then it kind of took over my life.

Given Trousdale’s history, did the fact that so little was written about it surprise you?

It did and it didn’t. Trousdale was becoming fashionable and pricey again; that’s usually enough for people to get interested in looking at the architecture, but I’m actually very proud to have put together the pieces to show just how many great L.A. architects were called on to build there in the ‘50s and ‘60s—and it was almost all of them, just a great concentration of big names in midcentury architecture.

One of the precepts of Trousdale was that its homes be designed by architects.

So the wealthy went to the best there were; old lions like Wallace Neff and Paul Revere Williams and James Dolena; new ones like A. Quincy Jones or Hal Levitt and Lloyd Wright. So I kept finding a Wallace Neff, a Cliff May, an A. Quincy Jones in Architectural Digest or other places, and began to put it together casually. When it became kind of a collection, I thought, I need to run with this, so I did.

The book also looks at social architecture of a city. Describe the social construct of Beverly Hills during the time that Trousdale Estates was conceived.

The backdrop is Southern Californian in the postwar era, full of growth and promise, a lot of optimism. It was a time of the Case Study House program, which showed the world how California lived. Those lessons were taken and expanded on by a lot of well-off Californians and developers. But if the California life was good in L.A., it was even bigger and better in Beverly Hills. Everything had to be bigger. I think a lot of people followed the Groucho Marx model.

He had lived in the flats of Beverly Hills, which is a somewhat conservative—architecturally, anyway— area. His brother Harpo lived there very comfortably all his life, but Groucho wanted to be free of it, so as this brand-new shiny development is going up above Beverly Hills, he decides to go there. He’s indicative of others who felt uncomfortable in traditional homes in the flats; they wanted to go to Trousdale to show their wealth, their power, their achievements—and they did. Self-made people who had made fortunes in their lifetimes wanted to reward themselves.

You write in the book that Trousdale was “long dismissed and derided as being all flash and no substance,” a notion that top L.A. architects helped dispel. Will you elaborate?

Architects followed clients, and clients followed fashion; they followed the news and what their neighbors were doing, and they followed, even then, celebrity culture, which was also a factor. Paul Trousdale wanted celebrities in his brand-new colony to publicize it and to make it desirable for other people, so when Dinah Shore moved in, when Groucho Marx moved in, when Barbara Stanwyck moved in, when Janet Gaynor moved in, all were very influential in having successful people want to be there and build there.

I think it’s attacked for its flash because, even though the homes were modern, they weren’t stripped-down modern. Trousdale has always been about excess and filling rooms with stuff, not trimmed-down living. It’s about absolutely everything.

I was surprised to learn about the number of Trousdale’s strict architectural codes during the early years—single-story homes with a minimum of 3,000 square feet to protect the views, for example. How did these restrictions evolve?

Some were relaxed in the 1980s. The change really was when the world moved away from modernism and remakes and historical styles started, especially down in the flats, where you see a kind of mishmash of French and Spanish and Italian style all together in one house. The changes were more stylistic.

Let’s talk about the teardowns at Trousdale. Is the practice common?

It unfortunately is. When I first started this, there were maybe 10 teardowns a year; now there’s probably 20 to 40. It’s hard because the lots are so valuable. Somebody can buy a house—5,000 to 7,000 square feet is now considered too small, by the way—but if the house has a view, no matter the architectural provenance, it may well be a goner.

Where do preservation efforts stand?

There are people who believe in restoring and loving great houses, but for the most part, it is about building anew at Trousdale, which, in a way, it always has been. At first, I thought that Paul Trousdale would be horrified by what was happening, and then I realized that, no, he actually would be very proud that what he built still has pizazz and attraction and is commanding top dollar.

But, you know, there are mechanisms in place, like the Beverly Hills Preservation Ordinance, which mandates that very notable houses be reviewed before they are altered or destroyed. We’re hoping to have one landmarked soon.

Let’s talk more about Paul Trousdale. Why was he able to negotiate the land deal for Trousdale as opposed to another?

I think it was his earlier ambitions, track record and just asking for it—he knew how to do it. And he probably got there first; he was incredibly well-connected. His progression of land deals got bigger and bigger, so he was one of the few who really knew how to do it, especially in difficult terrain.

When you have the San Fernando Valley, which is flat, or Torrance, which is flat, it’s easier to sub-divide, but he had to actually move mountains to make it happen, and not a lot of people had that experience.

Of all the amazing architecture in Trousdale Estates, which house do you feel is most deserving of “icon” status?

I probably have 10 favorites of every style. There’s Greek temple style, which defined the Caesar’s Palace era at Trousdale, but then there’s Ranch-style Trousdale, Hawaiian-Tropic-style and Hollywood Regency Trousdale—that was a very big thing in the ‘60s. Paul Trousdale himself had a home by Hollywood Regency godfather John Elgin Woolf, who was not thought to be a modernist, but actually did apply classic themes in modernist ways.

How many architectural styles are there at Trousdale?

Well, apart from the styles you expect—Post-and-Beam, Tropic-Modern, Greco-Roman Temple, or Neo-Formalist—Trousdale created a language of its own. Architects like Hal Levitt really came to define a new look for living, in that the most evocative homes often don’t really look like houses at all. They resemble museums, or banks, or country clubs, and I think that’s what the iconic Trousdale house is: cool, flat ceilinged and sculpted.

What features of Trousdale architecture support its aura of exclusivity and social achievement?

The first thing I think announced that in the early era was the application of marble on columns outside, and very tall double front doors. [Architect] Paul Williams said that you can tell the quality of a house by the height of its front doors; so they took that literally. The expanse of the carport—not garage, but carport—so that cars could be shown off to people driving by. They weren’t hidden away. In the back was always the pool, which you couldn’t see from the street but you knew was there.

The book also explores how Trousdale architecture responds to the mood of its various eras. Can you expand on this idea as it relates to the 1960s and 1970s?

The change that happened in the ‘70s resulted from the turmoil of the ‘60s. People began to look backward. Modernism entered the era of Charlie Manson. When openness became vulnerability, people really did seek to fortify. The new thing at the time was Spanish Modern. People called it nostalgia and the reclaiming of our architectural roots in Spanish architecture, but those heavy adobe walls and little bit narrower windows made people feel maybe a little bit less exposed. It was a fashion that was the follow up to Midcentury-Modern. And then that fell out of fashion. Everything is fashion.

Speaking of, we all know about the celebrities, the glamour. But what don’t we know? What surprised even you?

More than anything is the volume of A-list architects who built there. In the book I only had room to share about a quarter of what I actually have found. I’m amazed by the names, and I’m still finding more. Richard Dorman, William Stephenson, William Sutherland Beckett, Buff Straub & Hensman, Lundberg, Armet & Davis, Edward Fickett! Then the artful masters that perhaps never got as famous or whose stars have faded, like George MacLean, Rex Lotery, Amir Farr, Robert Earl, Harry Gesner, and now the stars of today like Marmol Radziner and the white-hot Paul McClean. I am also surprised at how much is being torn down at this moment. Mad Men has imbued a whole new generation with an appreciation for Midcentury-Modern; they want to know how it was lived at the top. I’m astonished that people are so very quick to tear down these things. It’s a constant battle… the freedom to build anew and build your own dream house is very much a factor in Los Angeles.

As a sociological document, what does Trousdale signify?

Aside from the movie stars and media giants, at one time, the heads of some of L.A.’s great merchant, manufacturing and conglomerate empires, both glamorous and ignoble, rewarded themselves with houses here: Gene Klein, who owned the Chargers. Cliff Garrett, whose company made the air pressure systems for the Mercury space program. Bob Six (with wife Audrey Meadows) who ran Continental Airlines. Irving Bulmash, who controlled S&H Green stamps. Barry Taper, of the banking family. Empires almost all now dissolved or recalled only in memories of those of us who grew up with them. Right now it signifies the big, new, what I call bling boxes. And I don’t mean that derogatorily. They are really fantastic showplaces. But the thinking is aspirational; the de facto motto of what is going up today is something extremely slick, stylish and with every luxury, from nightclubs inside to waterfalls to two-story garages with elevators. It’s just crazy. Homes are also designed by developers to sell to somebody. That’s the big difference, the retail aspect.

One thing I really was amazed to realize about Trousdale is that so many builders—Nathan Shapell (home builder who developed Porter Ranch), the Familian family, Montgomery Ross Fisher—people who could have lived anywhere, chose to build in Trousdale Estates. Not in one of their own developments, but in this one. That says something about what they were hoping to accomplish by building what they thought was a community of excellence—opulence too, but excellence—and I think that’s what people do today. Now that they’ve veered toward the $100 million mark, they’re going to try and exceed it with something showier and grander and glitzier. And that represents the aspirational people of today… people who really want to live well.

Photography Courtesy of Trousdale Estates by Steven M. Price