In a great many places art deco, the use of raw concrete is thought incredibly chic. A double trough-style sink, an expanse of floor, polished open shelving in an industrial loft—its unfinished look is everywhere, from commercial spaces to residential interiors, across the globe.

The popularity of the material brings one back around to Brutalism, the bold, blocky architectural style that derives its name from béton brut (French for “raw concrete”) and is in the throes of a revival thanks to serious preservation campaigns and digital platforms helping aestheticize it.

In truth, Brutalism needs no introduction; some buildings created in its geometricized, highly graphic vernacular predate World War II. But the movement boomed in the postwar world, reaching its peak from the 1950s to the 1970s. During this period, Brutalism was a prominent visual language in areas that experienced intense physical devastation (and a presence where there was none, namely the United States).

Its primary material proved an efficient and economical solution for reconstructing housing and civic buildings: concrete was cheap, it was durable, and for a prolific few decades, the obvious choice.

Not everyone warmed to this in-your-face form of Modernism, however—Brutalism was about monumentality and brought forth an aggressiveness that many found confounding and cold. Quite a lot of people simply hated it.

One must consider if, even unconsciously, the sense of indestructibility that underscored the style was an alienating reminder of the apparatus of war. Taking shape as it did (often in the form of government buildings), when it did (during the Cold War), it became easy for some to see a kind of Big Brother lurking in the stripped-down structures.

Eventually, it seemed like building after Brutalist building was, if not neglected, then met by the wrecking ball. Of the structures that stood, many boast some higher architectural value, including Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum in Dallas and Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation in Marseille.

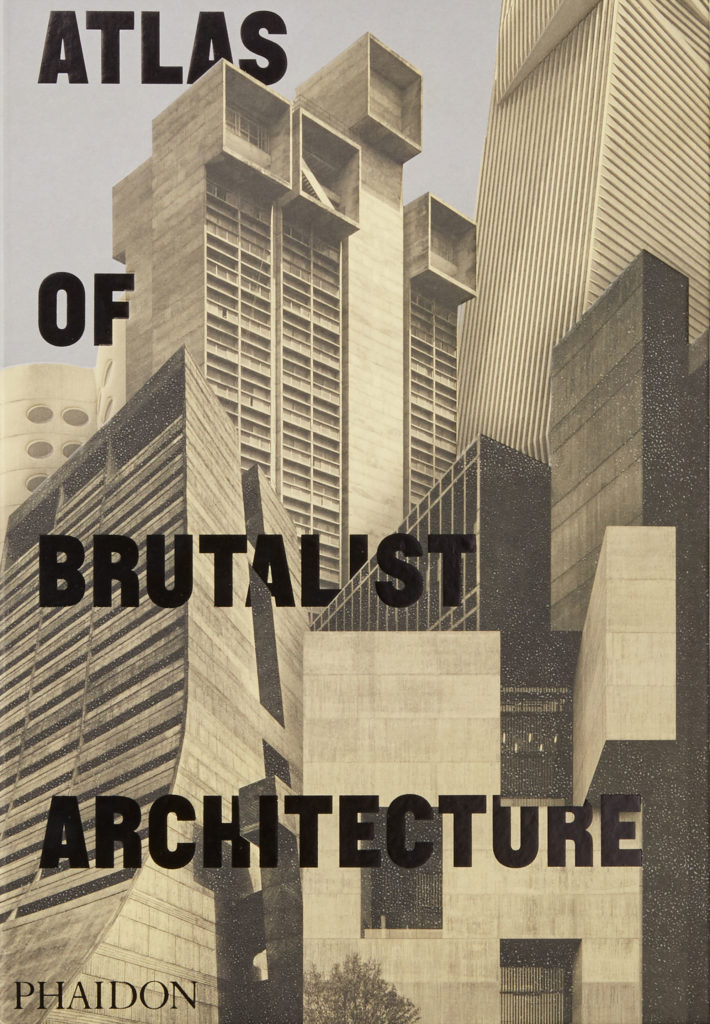

“Revulsion was certainly not a universal reaction [to Brutalism], and what is one era’s style is the next era’s eyesore, so in the midst of a demolition binge, a new generation is now learning to appreciate what is disappearing,” says Virginia McLeod, commission editor for Architecture and Design at Phaidon, which just released the Atlas of Brutalist Architecture.

“Demolition and destruction have brought Brutalist architecture to the attention of a wider public.”

Virginia McLeod

Along with Marcel Breuer’s defiant building that once housed the Whitney on Madison Avenue in New York and was sanctioned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art as the Met Breuer are preservation efforts across the pond. In northern England’s Sheffield, for example, a large part of Park Hill has been transformed into chic middle-class housing, while the Hayward Gallery in London has been subtly renovated.

Meanwhile, digital platforms like Instagram have fostered a more favorable appraisal of the

“I think it’s safe to say that there has never been an architectural movement that has so captured the public’s imagination—past and present,” says McLeod.

“I think it’s safe to say that there has never been an architectural movement that has so captured the public’s imagination—past and present,” says McLeod.

“The visual drama and emotional power of this bold, proud, ‘take-no-prisoners’ style of architecture, not to mention the acres of raw concrete in all of its limitless geometric permutations has, over the last decade,

All are fundamentally redefining Brutalism in a new age.

McLeod makes clear that, in or out of fashion, Brutalism has never stopped; indeed, it is alive and well.

“Today, Brutalist architecture is evident in the work of Steven Holl, Herzog & de Meuron, OMA, Grafton Architects and Zaha Hadid,” she says of just some of the architects who come from a generation that followed the vanguard Brutalists.

“And now, the current generation of young architects, including Pezo von Elrichshausen and Elemental, both from Chile, and

Aside from the derelict and demolished are Brutalist buildings with preservation or some form of protective orders. These range from a town hall and a post office to a number of churches and major cultural institutions. There are Lecture halls, a cinema, a ski resort and at least one water tower among many other structures.

The sheer array of these buildings, along with the digital revisions of the vernacular, speaks to the broader impact of Brutalism, then and now. What this says is largely up to the viewer. But as surely as Brutalism has played a role in the past, helping build, then rebuild, the modern world, it is a factor in the present.

PHOTOGRAPHS: (THIS PAGE AND NEXT) COURTESY OF PHAIDON