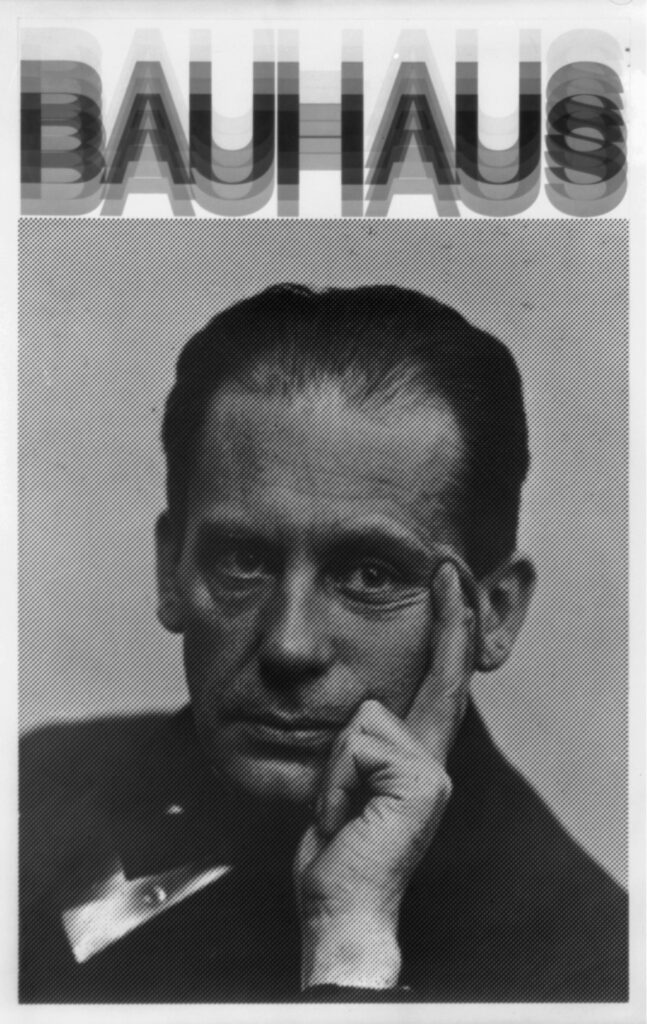

Walter Gropius An Early 20th Century German School Sought to Unify Art, Technology and Craft—Formulating New Approaches to Design That Live on as Far Away as Southern California Over a Hundred Years Later

Together let us conceive and create the new building of the future, which will embrace architecture and sculpture and painting in one unity and which will rise one day toward heaven from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith. Walter Gropius, in The Proclamation of the Bauhaus (1919).

It was fervid prose for a serious man—Walter Gropius, an architect and thinker in the early 20th century intent on training a new generation of creative workers who were fluent in synthesizing art and technology. He would achieve this, perhaps beyond his wildest dreams. His influence would extend for eons beyond the century in which he lived—and well beyond his native Germany.

At the time, at issue was how to maintain the ages-old rigor of fine craftsmanship in the face of the increasingly industrialized world. The answer for Walter Gropius wasn’t to diminish one for the other, he reasoned; rather, the two worlds could mutually build upon and benefit each other.

“Architects, sculptors, painters,” Walter Gropius instructed in The Proclamation of the Bauhaus (1919): “we must all turn to the crafts.”

Walter Gropius did more than propound, he created a powerful incubator for this to happen. And during its 14-year, often rocky run the Bauhaus would permanently change the worlds of architecture, fine art and design. Translated as the “house of building,” the school Walter Gropius founded ran from 1919 until 1933 and was first located in the city of Weimar, then in Dessau and Berlin before finally closing under pressure from the ruling Nazi party.

Walter Gropius and many leading figures of the Bauhaus—in architecture, most notably Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, as well as Marcel Breuer—would then find refuge in the United States, where their ideas would live on, their works flourishing and their teachings shaping subsequent generations of students and practitioners.

Whether segmented under the Modernist umbrella by way of International Style, Desert Modernism or Contemporary, the Bauhaus approach set in motion waves of design—and design thinking—that still remain alluringly au courant today. Over a hundred years later.

The Bauhaus presented a radical new approach to design—to the process itself, and to learning how to become a designer. Students freely explored new materials (steel, concrete, glass), and there was an emphasis on new forms that were unadorned, often starkly geometric and deployed with a singular mission—to serve humans efficiently in the brave new world of the 20th century. Recall that Germany, and the world, in 1919 were wracked by war.

With the signing of the Treaty of Versailles that year, perhaps the Bauhaus pioneers felt it was an ideal time to create the world anew. In aesthetics, it was also a time when embellishment, whether the theatrical Beaux-Arts or the gilded Baroque variety, was a de facto part of design, whether one was producing a building or a teapot. Speaking of the latter, the Bauhaus was not just for budding architects.

There were workshops in everything from furniture and textile design to photography, typography and even city planning. Functional design, the school held, did not happen in a silo. Unity was the school’s premise: whether it was joining usability with beauty; fine art and technical precision or creative mastery across a number of disciplines.

There was also a particular emphasis on transferring the painstaking standards of guild craftsmanship to the new modes of assembly line production taking place in factories. Stained glass. Stage design. Wall painting. Weaving. Carpentry and steel objects created for mass production. These were among the workshops at the Bauhaus, and it’s not surprising that many alumni were known for designing hit products across mediums.

“If he is to work in wood, for example, he must know his material thoroughly,” Grobius declared in The Theory and Organization of The Bauhaus (1923). “He must have a ‘feeling’ for wood. He must also understand its relation to other materials, to stone and glass and wool.”

Interior view, living room, Farnsworth House. Credit: Photographs in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

This avant-garde spirit carried across the Bauhaus campus. Students paraded paper lanterns they designed through the streets of Weimar. The improvisational musical stylings of the eclectic Bauhaus band were heard at artist festivals throughout Germany. And an evening program might consist of a concert given by composer Béla Bartók, or a lecture by astronomer Finlay Freundlich, then working with Einstein on relativity.

By 1933 the school had shuttered, but its ideas, methods of teaching and practitioners would propagate well beyond Germany. Walter Gropius would end up in Massachusetts, teaching at Harvard, where he became Chair of the Department of Architecture. By 1938 he built his personal residence in nearby Lincoln—Gropius House, now a National Landmark. It embodied the architectural premises of the Bauhaus: a structure of clean-line efficiency and simple beauty, born of natural light and strict utility in the service of its inhabitants.

It also became a well-known model of the emerging International Style of architecture, intriguing to the American public of the 1930s. So too was the wide-ranging Bauhaus exhibit at The Museum of Modern Art in late 1938. The exhibit was one of the museum’s largest to date, presenting almost 700 examples of the school’s works, from graphics and furniture to rugs, plates, paintings and architectural plans—and was a hit, drawing a record attendance.

For a while, Walter Gropius was joined in his architectural practice by Marcel Breuer, a protege from the Bauhaus who became a fellow faculty member at Harvard. (The two’s student roster is an American Who’s Who of Modernist architects that includes I. M. Pei, Paul Rudolph and Philip Johnson.) A famed architect and furniture innovator in his own right, among Breuer’s innovations are the well-known Wassily Chair and the Cesca Chair, both of which he designed while at the Bauhaus.

The former chair was admired by Bauhaus instructor Wassily Kandinsky, prompting Breuer to create a duplicate for the painter. Then there was the Chicago contingent. Mies van der Rohe, the last director of the Bauhaus before it closed, became head of the architecture school at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT).

His style articulated over the next few decades from his adopted hometown of Chicago, defined Jet Age utilitarian glamour in the form of sleek office towers and high-rise apartment buildings. He was joined in Chicago by another Bauhaus exile, the painter and photographer László Moholy-Nagy, who founded the New Bauhaus, which eventually became part of IIT. Like Gropius and Breuer at Harvard, their respective curriculums were game-changing for designers, and many of their teaching methods would become standard in art and design schools.

In the spring of 1961, a symposium at Columbia University’s School of Architecture honored four pillars of Modernist architecture. Le Corbusier. Frank Lloyd Wright. Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Walter Gropius. That two of its acknowledged leaders had been Bauhaus founding fathers, and now were among the most vital and influential architects in America, must have been a keen triumph for the two men.

A satisfying confirmation that their ideas were being realized on a broad and eager scale, in countless buildings and homes constructed far from the Bauhaus. Even those as far away as Southern California, where the sun-soaked desert and coastal communities still present a perfect canvas for those Bauhaus buildings of the future, described by Walter Gropius over a hundred years ago—sheathed in steel and glass, framing otherworldly natural scenes and rising “from the hands of a million workers like the crystal symbol of a new faith.”